Polynomial conjoint measurement

Polynomial conjoint measurement is an extension of the theory of conjoint measurement to three or more attributes. It was initially developed by the mathematical psychologists David Krantz (1968) and Amos Tversky (1967). The theory was given a comprehensive mathematical exposition in the first volume of Foundations of Measurement (Krantz, Luce, Suppes & Tversky, 1971), which Krantz and Tversky wrote in collaboration with the mathematical psychologist R. Duncan Luce and philosopher Patrick Suppes. Krantz & Tversky (1971) also published a non-technical paper on polynomial conjoint measurement for behavioural scientists in the journal Psychological Review.

As with the theory of conjoint measurement, the significance of polynomial conjoint measurement lies in the quantification of natural attributes in the absence of concatenation operations. Polynomial conjoint measurement differs from the two attribute case discovered by Luce & Tukey (1964) in that more complex composition rules are involved.

Contents |

Polynomial conjoint measurement

Krantz's (1968) schema

Most scientific theories involve more than just two attributes; and thus the two variable case of conjoint measurement has rather limited scope. Moreover, contrary to the theory of n - component conjoint measurement, many attributes are non-additive compositions of other attributes (Krantz, et al., 1971). Krantz (1968) proposed a general schema to ascertain the sufficient set of cancellation axioms for a class of polynomial combination rules he called simple polynomials. The formal definition of this schema given by Krantz, et al., (1971, p.328) is as follows.

Let  . The set

. The set  is the smallest set of simple polynomials such that:

is the smallest set of simple polynomials such that:

;

; such that

such that  and

and  , then

, then  and

and  are in

are in  .

.

Informally, the schema argues: a) single attributes are simple polynomials; b) if G1 and G2 are simple polynomials that are disjoint (i.e. have no attributes in common), then G1 + G2 and G1  G2 are simple polynomials; and c) no polynomials are simple except as given by a) and b).

G2 are simple polynomials; and c) no polynomials are simple except as given by a) and b).

Let A, P and U be single disjoint attributes. From Krantz’s (1968) schema it follows that four classes of simple polynomials in three variables exist which contain a total of eight simple polynomials:

- Additive:

;

; - Distributive:

; plus 2 others obtained by interchanging A, P and U;

; plus 2 others obtained by interchanging A, P and U; - Dual distributive:

plus 2 others as per above;

plus 2 others as per above; - Multiplicative:

.

.

Krantz’s (1968) schema can be used to construct simple polynomials of greater numbers of attributes. For example, if D is a single variable disjoint to A, B, and C then three classes of simple polynomials in four variables are A + B + C + D, D + (B + AC) and D + ABC. This procedure can be employed for any finite number of variables. A simple test is that a simple polynomial can be ‘split’ into either a product or sum of two smaller, disjoint simple polynomials. These polynomials can be further ‘split’ until single variables are obtained. An expression not amenable to ‘splitting’ in this manner is not a simple polynomial (e.g. AB + BC + AC (Krantz & Tversky, 1971)).

Axioms

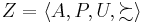

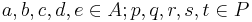

Let  ,

,  and

and  be non-empty and disjoint sets. Let "

be non-empty and disjoint sets. Let "  " be a simple order. Krantz et al. (1971) argued the quadruple

" be a simple order. Krantz et al. (1971) argued the quadruple  is a polynomial conjoint system if and only if the following axioms hold.

is a polynomial conjoint system if and only if the following axioms hold.

- WEAK ORDER.

- SINGLE CANCELLATION. The relation "

" satisfies single cancellation upon A whenever

" satisfies single cancellation upon A whenever  if and only if

if and only if  holds for all

holds for all  and

and  . Single cancellation upon P and U is similarly defined.

. Single cancellation upon P and U is similarly defined.

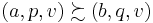

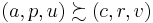

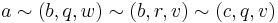

- DOUBLE CANCELLATION. The relation "

" upon

" upon  satisfies double cancellation if and only if for all

satisfies double cancellation if and only if for all  and

and  ,

,  and

and  therefore

therefore  is true for all

is true for all  . The condition holds similarly upon

. The condition holds similarly upon  and

and  .

.

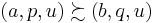

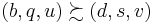

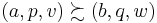

- JOINT SINGLE CANCELLATION. The relation "

" upon

" upon  satisfies joint single cancellation such that

satisfies joint single cancellation such that  if and only if

if and only if  is true for all

is true for all  and

and  . Joint independence is similarly defined for

. Joint independence is similarly defined for  and

and  .

.

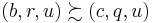

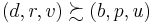

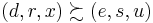

- DISTRIBUTIVE CANCELLATION. Distributive cancellation holds upon

if and only if

if and only if  ,

,  and

and  implies

implies  is true for all

is true for all  and

and  .

.

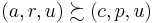

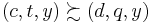

- DUAL DISTRIBUTIVE CANCELLATION. Dual distributive cancellation holds upon

if and only if

if and only if

,

,  ,

,  and

and  implies

implies  is true for all

is true for all  and

and  .

.

- SOLVABILITY. The relation "

" upon

" upon  is solvable if and only if for all

is solvable if and only if for all  and

and  , there exists

, there exists  and

and  such that

such that  .

.

- ARCHIMEDEAN CONDITION.

Representation theorems

The quadruple  falls into one class of three variable simple polynomials by virtue of the joint single cancellation axiom.

falls into one class of three variable simple polynomials by virtue of the joint single cancellation axiom.

References

- Krantz, D.H. (1968). A survey of measurement theory. In G.B. Danzig & A.F. Veinott (Eds.), Mathematics of the Decision Sciences, part 2 (pp.314-350). Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society.

- Krantz, D.H.; Luce, R.D; Suppes, P. & Tversky, A. (1971). Foundations of Measurement, Vol. I: Additive and polynomial representations. New York: Academic Press.

- Krantz, D.H. & Tversky, A. (1971). Conjoint measurement analysis of composition rules in psychology. Psychological Review, 78, 151-169.

- Luce, R.D. & Tukey, J.W. (1964). Simultaneous conjoint measurement: a new scale type of fundamental measurement. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 1, 1-27.

- Tversky, A. (1967). A general theory of polynomial conjoint measurement. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 4, 1-20.